France's prominent magazine Le Point, has featured ILD's Hernando de Soto with a portrait interview in their January 2016 issue. The feature highlights the work of Hernando on the informal economy and takes a special look on his work in the MENA region in regards to the Arab Spring.

Here is a translated version of the article:

-------------------

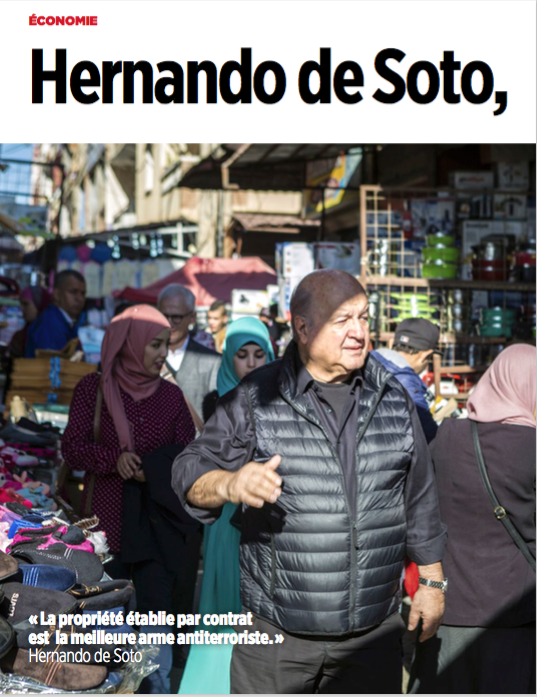

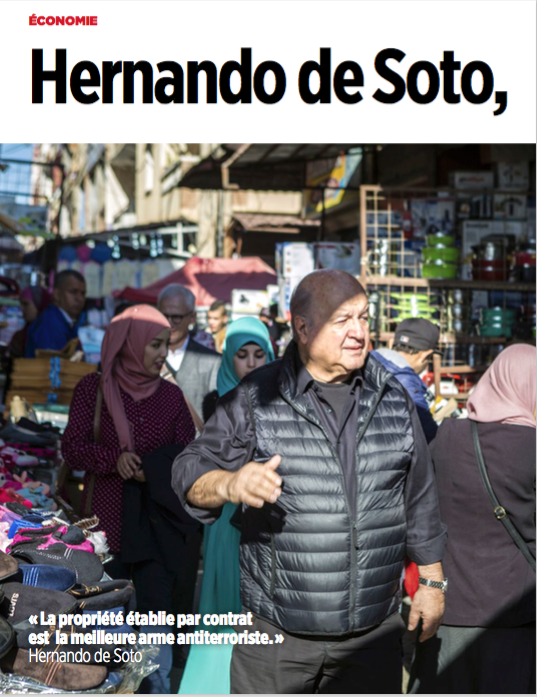

The iconoclast. The Peruvian economist believes in liberal reforms to eradicate poverty and terrorism. A portrait of a deeply practical man.

BY LUC DE BAROCHEZ, SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT IN ALGIERS

BY LUC DE BAROCHEZ, SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT IN ALGIERS

He points to a pile of concrete blocks on the pavement of a dirty street in the suburbs of Algiers, where he is speaking at a conference. “That,” according to the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto, “is where people put their savings in the informal sector.” A pile of abandoned blocks under the winter sun, next to a building with only the first three stories completed, is a pretty common sight in a developing country. But what Hernando de Soto sees in this pile of blocks is just how distorted the informal economy is and, by implication, the real drama of underdevelopment.

The person erecting the building has no official property rights to the land. These are too complicated to obtain from a Kafkaesque bureaucracy and too expensive because of all the palms to be greased. Not to mention the humiliation of all the various forms of protection you need to beg for. Besides, there is often no land register to speak of. Without any legal title the owner cannot obtain any credit, so it makes sense for them to plough their money into the construction of their building as and when they earn it. A process that sometimes takes a lifetime. This is why savings are turned into concrete blocks and bags of cement rather than placed in life insurance policies or savings accounts. But savings used in this way cannot fulfill their main function of financing the wider economy. It is dead money, effectively.

Just like the dark matter which makes up the majority of the universe, the informal economy acts – unseen – as a deadweight on development. For 74-year-old de Soto, who was described by US President Bill Clinton a few years ago as "the greatest living economist" and whose investigative work has taken him to the dusty backyards and dingy stairwells of Lima, Cairo, and Algiers, up to 90% of the economic actors in these countries can be found in the informal sector. What is missing is documentation: the poor have plenty of capital, but lack legal title. Giving them these documents would free up “dead capital” to finance new businesses or construction projects and start a virtuous circle of development and growth.

In Egypt, for example, a study conducted by the economist showed that some 24 million workers received 21 billion dollars in wages during 2013, while owning 360 billion dollars of capital not legally recognized – 17 times as high as the wages figure, in other words. For Egypt, this "dead capital" is equivalent to 100 years of aid spent on development, military, and financial purposes!The feeling of being excluded from the legal economy can drive people to take extreme action, and this is something Hernando de Soto tried to quantify in his investigation into the death of Mohamed Bouazizi. This 26-year-old Tunisian man, a market trader selling vegetables, set fire to himself on December 17, 2010, at Sidi Bouzid because the authorities had confiscated his barrow and electronic scales. The economist has counted 63 other cases of people trying to set fire to themselves in the two months after this event, both in Tunisia and five other countries in the region. These desperate acts sparked the Arab Spring and the destabilization of much of the Middle East.

“Expropriated by the State”: Under the auspices of the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), which he heads in Lima, and in partnership with Utica, an organization representing business people in Tunisia, Hernando de Soto sent around 30 students and experts to interview the relatives of those who died after setting fire to themselves and those who survived such episodes in order to understand what made them do it. “What struck me,” he recalls, “is that none of those interviewed gave any political or religious reason by way of explanation for these actions. They only wanted to talk about the administration which had robbed them and their frustrated desire to escape from poverty. These were business people whose assets had been expropriated by the State and who were protesting accordingly.

”Mohamed Bouazizi could not pay for his confiscated merchandise and was unable to sell his business either and set up elsewhere because he had no legal title to assign. He died as a result of the fire, dressed in his Western-style clothes of T-shirt, Nike sneakers, jeans, and bomber jacket: a kind of testament to his aspirations to live in a legal and modern market economy. “Those who work in the informal economy don’t turn their backs on the law,” points out Hernando de Soto, “it’s the law that turns its back on them.” And for every few committing suicide, there are thousands becoming radicalized. “Property rights established by contract are the best weapon against terrorism,” he affirms.

A big, charismatic man, Hernando de Soto’s enthusiasm is contagious. When In Algiers or Tunis he expresses himself in immaculate French, a language he learnt in Swiss schools when his father, who had been exiled and run out of Lima after a coup, was working for the International Labour Organization in Geneva. He only returned to Peru in 1979, at the age of 38, after an earlier career as a businessman in Switzerland. He found Latin America more accommodating than Europe because there “you don’t need a CV to make your voice heard.” But the country he found was backwards, poor, and stuck in its ways. One question would nag away at him: why is Peru not as rich and prosperous as Switzerland, even though Peruvians are just as smart and enterprising as the Swiss?

To help him get to grips with this conundrum, he tried to set up a workshop for manufacturing T-shirts and commissioned a lawyer to deal with the various procedural aspects. “This took him 278 days, working 8 hours a day,” he remembers. He realized the obstacles to capitalism were hindering development. He found himself at loggerheads with the Maoist guerrilla organization which was bleeding the Peruvian countryside dry at the time and which believed the problem was capitalism itself. In 1986 he published The Other Path, whose title amounted to a declaration of war against the terrorists of the Shining Path. Having become an advisor to President Fujimori, the economist set about implementing his blueprint: wholesale reforms, no red tape, simpler procedures, registration of property, greater freedom for business, and a more fluid market. The Maoists tried to assassinate him at least three times. His institute was attacked with Kalashnikovs. A car bomb exploded outside his building killing several people. Then his own car was riddled with bullets. Each time he managed to escape with his life. Hernando de Soto encouraged the Indian peasant populations to form militias when he recognized their traditional rights to own property and bear arms. Within a few years the Shining Path had been defeated. Since then Peru has experienced something of an economic miracle, growing twice as quickly as the rest of Latin America.

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, the battle waged by Hernando de Soto took on a global dimension. He now believes the military response by the United States, which has already cost them 1,600 billion dollars, to have been a failure. Jihadist organizations simply keep on growing. Faced with the prospect of the Islamic State, the Peruvian economist recommends “winning hearts and minds” – the credo espoused by the military involved in counter-insurgency campaigns – by offering the disenfranchised some kind of hope again in terms of their economic prospects. He has become a favorite adviser of the powerful, with invitations coming from Colombia, Mexico, El Salvador, the Philippines, Indonesia, Ghana, and Tanzania. But his work mainly takes him to Arab countries these days. Islamic State and the like can be defeated, as he never tires of explaining. Not with bombs, but with liberal reforms. What the elites of the North struggle to understand, he feels, is why the key to success is not the protection of property rights established in law and backed up by a redistributive system. On the contrary – it is a case of recognizing informal and illegal rights. The kind that no one really wants to talk about.

Today’s Mohamed Bouazizis are really just latter-day Jean Valjeans (from Les Misérables) or David Copperfields. The developing countries need to rediscover the nineteenth century blueprint that enabled Europe, followed by the United States, to create wealth out of nothing. At the time it was a case of those excluded from the aristocratic system turning the powerfully liberating effect of free trade and the vouchsafing of property rights to their own advantage.

The blueprint is well established: the rule of law, free enterprise, respect for property, an independent judiciary, and representative democracy. It goes without saying that this prodigious but fragile ecosystem will not be able to blossom under the kinds of autocratic and corrupt regimes too often found in Arab countries. As Hernando de Soto puts it: “Democracy is a very important complementary element, because you’ll always have some people trying to make money at the expense of others. Elective democracy, provided those elected represent a given constituency rather than being picked by parties, is the way to temper the excesses of capitalism.”

“Excluded from the game”

Of the 7.3 billion people in the world, less than a billion live in industrialized countries. De Soto has calculated there is another billion like him who belong to the globalized elites of the South. “This leaves more than five billion people excluded from the game. Five billion without the property rights – enshrined in law – which would enable them to create wealth by themselves.” As far as he is concerned, those attempting to attribute inequality to religion are making a terrible mistake. In order to combat this kind of inequality, it is essential not to rein in the process of globalization. Quite the opposite, if anything. Europe must defend its culture, its tolerant attitude, and its capacity for inclusion, since these are things which really appeal to the dispossessed and persecuted – and represent a threat to the terrorists. At the same time, the majority of the population must be given the opportunity to acquire property rights that can be "traded" with a view to generating credit and building up the capital required to make investments. "Pope Francis, a Latin American like me, asks why so few people have so much money. But this is a loaded question. I’m tempted to ask why so many people have so little money. If you put the question like this, you'll get a different answer, but a no less important one."

Read the whole French portrait interview with Le Point